09 Mar “Othering” in Land Conservation

9 March 2021

By David Allen, Development for Conservation

Several years ago, Vu Le (Non-Profit AF) wrote a critique of donor-centric fundraising. In the several weeks that followed, I wrote a critique of his critique, arguing that Le’s definition of donor-centric fundraising was based on several inaccuracies. That post, What is a Donor? And What is “Donor-Centric”?, remains the most widely read essay I have ever written and still enjoys readership every week.

I wrote another post several weeks later on the concept of “othering,” based on a second, important point in Le’s post, and it seems timely to revisit that idea today. Most of this is an update from that post in 2017.

Here is the paragraph from Le’s critique:

[Donor centrism] perpetuates the othering of the people we serve: An insidious effect of the Savior complex is that people see other people as “others.” “Others” exist in our minds in a binary state, either as enemies, or as those to be helped, never our equals. With this current political climate, we’ve been seeing a lot of people perceiving and treating fellow human beings as “others/enemies.” But the “Others/People-to-be-helped” mindset is also destructive……We cannot build a strong and just society if we reinforce in donors the unconscious perception of the people we help as merely objects of pity and charity to be saved.

You might react, as I did on first reading, that this doesn’t really apply in the conservation community.

But we’d both be wrong.

In the spirit of “language matters,” let’s look at three words that we use very commonly and that betray our “othering” tendencies. The three words are “educate,” “protect,” and “landowner.”

Educate

In nearly every strategic planning exercise with which I have been involved over the past 20 years, someone has added a strategy or a goal that has something to do with “educating the public.” The underlying frame of reference is that the public doesn’t know what’s good for them or what solutions might be out there for their particular issues and problems. We do! We have science and technology and GIS, and together with two scoops of hubris, we’re well positioned to show them exactly what to do in their own best interest. We just need to educate them.

They just need to be educated.

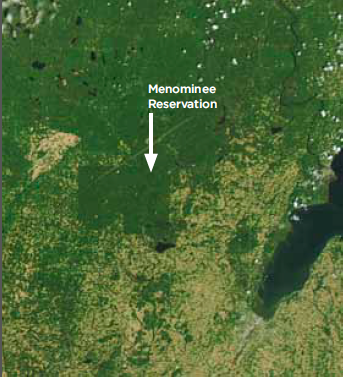

We barely get away with this in a culture that is predominantly white (not to mention the current political climate trending to anti-science). Many of us have come to understand that we don’t have a chance in Native American communities, but we still believe that African American and Latino cultures are disinterested, apathetic, ignorant, or some combination of all three. Collectively, they (including the ignorant whites) are all “others” needing to be educated.

And our educational offerings are all based on the same premise: find a local expert and have them “teach” us about whatever field they are expert in – usually in the form of classroom-style lectures or guided field explorations. And the people who respond to this type of opportunity are most often educated whites who are comfortable in that environment.

When reaching out into non-white communities, we talk about needing to listen first. Not that it’s bad advice necessarily, but the underlying – “othering” – assumption is that if we listen hard enough, we will find places where we can teach them to use our solutions to fit their problems.

They just need to be educated.

What about the possibility that they might offer a solution to something we’re working on? Are we willing to listen that hard? To approach them as equals? How do we learn to listen for wisdom we can apply for ourselves instead of just ideas that connect to our solutions for them?

Le calls this kind of othering an “insidious effect of the Savior complex,” and he’s right.

What if we changed the language? What if we talked more about “engagement” or even “mutual learning opportunities” instead of education?

Protect

The word “protect,” of course is embedded in everything we do. If land is colored green (or sometimes brown) on a map, we interpret that to mean it is protected. If land is white or some other color, it is referred to as a “gap” between protected areas – ie. “unprotected.” In fact, both ideas depend on some amazing assumptions – that land in public or non-profit ownership is protected and that land in private ownership is not.

It turns out to be pretty easy to disprove both. Strip mining, clear-cutting, lethal predator removal, controlled development, and even outright sale of protected properties aren’t unheard of on land owned by federal and state agencies. And the strength of land trust conservation easements is certain to be increasingly tested over time.

And talk to western and southwestern ranchers about whether the land that has been in their family’s continuous ownership since the civil war is protected or not.

To be sure, there are “levels of protection,” but as a conservation culture we use the word far too freely and cavalierly.

For one thing “protection” implies a singular act. What we really mean is that the land is in nonprofit or public ownership. And we proudly claim credit for having “protected” numbers of properties and acres. Any land steward will tell you that land protection is an ongoing challenge.

What if we changed the language? Instead of land that we have “protected,” how would it change perceptions if we talked about land that we are caring for, stewarding, restoring, or managing for habitat – and never even mentioned land that we had protected?

Citizens for Conservation, an Illinois land trust, talks about “saving living spaces for living things.” I like that a lot.

Landowner

We use the word “landowner” all the time, and most of the time, it’s completely fine because it describes the literal truth. But what about landowners on whose land we have easements?

An easement landowner is too often considered almost as an adversary – someone we tolerate, monitor, and occasionally sue as necessary to prevent them from doing something contrary to our interests.

An “other.”

We can educate them first and then help them protect their land.

But what if we started inviting them into the center? As equals. As partners.

What if we referred to easement landowners from day one as “conservation partners”? What if every interaction returned to the agreed-upon conservation values for context instead of potential violations?

What if the line below which they signed their name on the monitoring form read: Conservation Partner?

So, here’s how all this applies to donors and donor-centric fundraising: We need to be careful not to practice “othering” on donors, too.

The mission is at the center. Science is at the center. The staff and Board are at the center. The volunteers are at the center. And for land conservation, the land and water and all the critters they support (including humans) are at the center.

The problem with our donor communication (letters, newsletters, website material, even Facebook and other social media) is that it is written as if the reader/donor is NOT part of the center.

In other words, that donors are “others” too.

They just need to be educated.

Cheers, and Have a great week!

-da

PS: Your comments on these posts are welcomed and warmly requested. If you have not posted a comment before, or if you are using a new email address, please know that there may be a delay in seeing your posted comment. That’s my SPAM defense at work. I approve all comments as soon as I am able during the day.

Photo by Fred Ménagé courtesy of Pixabay.

Nate Lewis

Posted at 12:00h, 25 MarchIntrigued by the conversation about the word “steward” and its connotations. On one hand, I’m always referring to my wife and myself as “stewards” of the sacred lands of the Squaxin Island Tribe (we farm land in South Puget Sound, WA). On the other hand, the “stewardship” part of land trust activities can establish an adversarial role between current occupants of the land we’re charged to “steward.” I’m excited to think about how “stewardship” activities can also go hand in hand with collaborative learning experiences. We’re squarely focused on preserving farmland, so have a different bent on the issue, but there’s still a lot of crossover.

Mary Ellen Wuellner

Posted at 10:36h, 12 MarchLike Carol, I shared this broadly across our organization. Thank you for this article. We do fall into this trap, more often than I care to admit.

peterpetermckeevernet

Posted at 13:34h, 10 MarchDavid,

You wrote: “What about the possibility that they [others]might offer a solution to something we’re working on? Are we willing to listen that hard? To approach them as equals? How do we learn to listen for wisdom we can apply for ourselves instead of just ideas that connect to our solutions for them?

That brought to mind Barry Lopez’ observation in his final and remarkable book “Horizons” that of the many field investigations he was privileged to participate in over his career …anthropological, archaeological, climatological, ecological…in many places in the world, including the High Artic, Africa, Antarctica, Australia, South America and North America, he had rarely been on one in which the scientists invited local indigenous people to participate. He suggested, as you do, that those doing the field work might have learned something from those who lived there for generations. They often see things differently, both literally and figuratively.

In our work, they might also be the constituency that will protect the land in the future if they are engaged.

David Allen

Posted at 14:47h, 10 MarchWell said, Peter.

Judy Anderson

Posted at 09:34h, 09 MarchDavid, agreed. There is a top-down tendency in the land conservation effort to “know what is best.” If you read the newsletters, strategic plans, websites, one sees a lot of “we know this, you need to know and do this.” Combine that with jargon, and as you say “othering” and it can be very off-putting. That’s why I have spent so much time working on language and imaging. Landowner is classic. So is Stewardship. Conservation Easement. Private Land Protection. These are all terms that distance readers from the story of change. I often suggest that it’s important to describe, rather than tell; to ensure that readers (rather than just donors) feel part of the change because they share the values of that change. And, as you point out, that means thinking about how they are experiencing life, and listening to how we can help.

To educate is an arrogant perspective. We need to understand that connection is the first step to creating an ethic of caring, compassion, and curiosity.

So too is the presumption that education means people will care. The data doesn’t support that. We might want to shift to thinking about how we can do more to build empathy, compassion, and joyful experiences that build a sense of community with those who haven’t had much chance to experience that–or with others.

I’ve started asking land trusts “how selfish are you”? That doesn’t go over well, but the concept is this: Who are you serving? Why? Who has been left out? How are you offering to assist the community, rather than asking the community to assist you? That addresses the “othering” concept when you work with, partner with, those in your community on a project that they want and need.

Kimberly Gleffe

Posted at 09:00h, 09 MarchWords sure do have power and we certainly do need to be aware and careful about their use. I like the options for changing the language. And was also reminded of an adverse feeling I had when listening to a nonprofit leader (I shall keep nameless) defending a proposal to the WI Coastal Management Program… saying THEY need to be EDUCATED about how to manage stormwater because THEY don’t know what to do about it…. sigh.

Thanks, as always, for your good insight.

Carol Abrahamzon

Posted at 08:33h, 09 MarchAs I began to read this I thought, our new DEI committee needs to read this, then as I read on I thought, Oh and our communications committee too. In the end…everyone needs to read this. Thank you!

Jill Boullion

Posted at 08:17h, 09 MarchWe’ve been having a lot of discussion at our land trust about privilege and all the ways that it manifests. We’ve yet to move beyond thinking about how we engage with people in the community that are normally outside our circle to how we manifest our privilege when considering land protection and stewardship, so your insights are really valuable. Thank you.

Robert Ross

Posted at 07:56h, 09 MarchThe word “steward” also conveys superiority — a wine steward tells people what champagne to serve at a wedding for example. Development folks often “steward donors”; better might be “nurture donors”.

David Allen

Posted at 13:58h, 09 MarchThank you. I am honored by your comment, Bob. And thank you for your work with Big Apple Greeters!

Robert C. Ross

Posted at 17:07h, 09 MarchThanks David. Big Apple Greeter was the first Starter Kit charity, and there are now 42, including five land trusts. Always looking for other worthy charities who might be interested in this interesting approach to Planned Giving.

Brianna Dunlap

Posted at 11:11h, 11 MarchHello Robert, and everyone.

I would like to offer a counterpoint on the term “steward”, as used with land trusts in general. I think that it is becoming more popular as an inclusive term because not everyone who tends to land is the landowner.

Someone can be an absentee landowner, but a land steward is someone who is involved with the earth body and spirit.

I know that this post is about donor-relations, however the term is evolving, and worth the share.

Robert C. Ross

Posted at 11:47h, 11 MarchI agree that “steward”, “stewardship”, and other variants of the word make great good sense in the narrow sense of caring for land. Great expertise is clearly required, and in New Jersey under the Green Acres program, the regulations use that very word to meet the requirement that a land trust commit to steward a property that will be acquired under the statute, i.e. to protect the land from development after the acquisition.

My objection is using the word in the context of a development officer “stewarding” donors. As a donor, it offends me, it makes me feel that the development officer thinks they know better than I do how I should donate my money. When I discuss the word with other donors, I have almost invariably found the same negative reaction to the word.

It also, I believe, inhibits development officers from focusing on what the donor wants, often prevents them from asking the most powerful questions I’ve found when I put on my fund raising hat: “Why do you support this charity.” or “What charities are important to you.”

It’s amazing to me how many donors and potential donors have told me they have never been asked those questions.

reneecarey

Posted at 07:55h, 09 MarchAs I read more, learn about other perspectives, and think more, I recognize we in the conservation community need to do a lot more listening. Forget about educating the public we need to be educated on our biases and how they influence what we do, how we do it, and how we communicate about it.

Words have meaning and power. Words send messages and signals. We need to understand what we intend may not be the impact they have.

David Allen

Posted at 07:59h, 09 MarchRenee, Thank you so much for this comment. I have been thinking, over breakfast this morning, that changing our language may serve an important role in changing how people relate to us and to land conservation generally. But a much more consequential outcome might be that changing our language has the potential to change how we see ourselves and relate to other people.

Lisa Haderlein

Posted at 07:45h, 09 MarchDavid, I think this is the most important piece you’ve written. You articulate the challenge so well. Thank you for all you do.